Strong Southwestern Sisters

Laura Kuykendall, SU’s first dean of Women and one of SU’s first female drivers; photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Ever stroll through the Southwestern University campus? Go ahead—”townies” are welcome to enjoy the beautiful old and new buildings and reflect on a history of Georgetown support for its highly rated hometown university.

The 16th and first female, SU President Laura Skandera Trombley

And for those who appreciate that women are ever gaining an equitable position in our culture, enjoy the fact that Southwestern University now has its first female president! Learn more about awesome President Laura Skandera Trombley here. She’s a seasoned leader and Mark Twain expert and writes about equity in academia and much more.

A good place to start is the lovely Lois Perkins Chapel.

Lois Craddock Perkins

Lois Craddock came to Southwestern in 1908 from tiny China Springs, Texas, near Waco. She had some tough going growing up: Her mother died early, and she took on the task of raising her siblings.

She studied at Southwestern for three years; illness kept her from getting a degree. Nonetheless, she taught school in Wichita Falls with the hope, she wrote, of giving back some of what she got from her beloved SU days.

She also married wealthy businessman Joe Perkins, and together they gave much money to Methodist schools such as Southwestern—including funding the Lois Perkins Aid Fund for Young Women at Southwestern. The pair donated a total of $12 million toward the School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas; the school was then named the Perkins School of Theology.

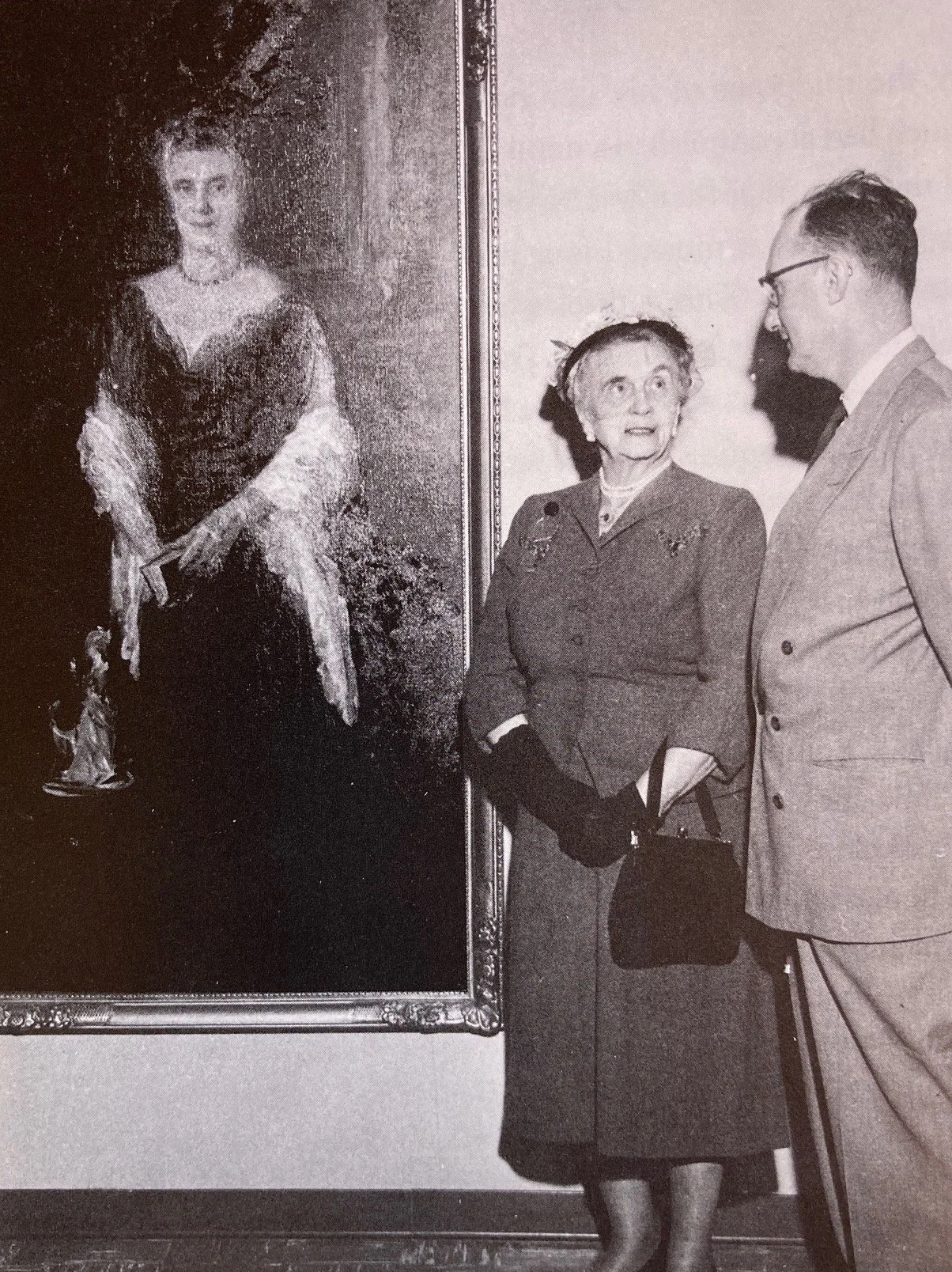

Lois and Joe Perkins look at a drawing of the chapel they funded. Photo from the 1944 Southwestern University yearbook, The Sou’wester

But when Joe was informed in 1952 that five Black students were attending the Perkins theology school, he was not happy. The time was not yet right for integration, he said, instructing the Dean (who was in favor of integration) to “get rid of the Negroes as soon as possible.” When the matter came up later, Lois told the Dean that “I don’t agree with my husband on this matter.”

Perkins Black pioneers graduating in 1955: (L-R) James Arthur Hawkins, John Wesley Elliott, Negail Rudolph Riley, Allen Cecil Williams, and James Vernon Lyles

The Black students stayed and graduated, and much credit is due to Lois. And The Perkins School became the site of the first voluntary desegregation of a major educational institution in the South.

Lois Craddock Perkins pushed for equality.

Lois continued to quietly but firmly push for integration at the theology school. When the following dean nervously allowed interracial roommates (something students wanted), he feared more backlash from donors and parents. But Lois made it clear that’s what needed to happen.

As Kevin M. Watson writes in his article on the desegregation of the Perkins school, Lois said, “Now isn’t that grand? We’ve taken another step, and this is something we can be grateful for. Perkins is known around the world as a progressive school . . . Besides, what would I tell my Women’s Society in Wichita Falls if we went back on this advance?” Lois’s actions exemplify, Watson writes, the important role of Methodist women in advancing racial equality and other causes. This trait of women’s activism is also true for other denominations and faiths.

The ladies make a point.

Another interesting note from the Perkins past: Women were admitted before Black students were, but females in the early years say they felt ignored and not as valued as male students. When the admitted Perkins students of 1969 gathered for a photo, the instructions sent to all the students told them to wear coat and tie. The ladies, making the point that they were graduate students as well, all wore coat and ties!

The Racial History of Southwestern

Southwestern, like Georgetown and other places in the South and US, has a history of racism and segregation. Like most US universities built before or during the Civil War, the colleges that merged to form Southwestern used the work of enslaved people to build and embraced the Confederacy. Many of the prominent families who supported SU also supported the Confederacy and some owned enslaved people.

Learn much more in this excellent website of the Southwestern University Racial History Project. Faculty members and students unfold the racial journey of the four Texas colleges that coalesced to form Southwestern along with SU’s racial journey, and call for continuing work to make SU welcoming to all.

The Placing Memory website is a student-written collection of stories about SU spots and histories, including the racial practices of the four root schools. Students call for a more visible profile of SU’s racial history.

Look to the east side of the chapel in the courtyard for this sculpture, called Madonna and Child.

Margarett had this made for her mother.

Margarett Root donated this sculpture by noted Austin sculptor Charles Umlauff in the memory of her mother, South Carolina Easley Root. As is too frequently the case with women, “not much is known” of South Carolina.

But Margarett was a pistol. Raised on a farm outside Georgetown, she pursued arts and literature at Southwestern and was involved in many campus doings and excursions.

Margarett Root Brown

After graduation, she taught school in Belton and in 1917, she met Herman Brown, who’d started a road paving business, at a Georgetown dance. Margarett and Herman eloped a few months later, but for their wedding, reports the Texas State Historical Association, Margarett “would not accept a wedding ring because she thought of it as a sign of bondage.” The couple spent their honeymoon in one of Herman’s road construction tents.

Margarett’s brother, Dan, who had become a prosperous cotton farmer, invested in Herman’s business that was called Brown and Root. Margarett was a Brown and Root partner as it grew into the firm still prominent today as a worldwide industrial services company constructing everything from ships to oilfield equipment.

She also kept up the cultural pursuits she’d loved at SU, participating in the local Woman’s Club and in the Bronté Club, the state’s oldest women’s literary society. The Bronté Club started in Victoria, Texas, in 1855; members founded and grew the Victoria city library.

Margarett was a founder of the Brown Foundation, which has given $1.7 billion in grants to educational, cultural, and civic projects. The Brown Foundation funded the Brown-Cody Residence Hall, which was built in honor of three women whose donations funded endowments and facilities and landscape features throughout the SU campus. Margarett (class of 1915) is one of the three honored, along with Alice Pratt Brown (class of 1924; Alice was a major funder of the Houston Museum of Fine Arts and a close buddy of Lady Bird Johnson) and Florence Root Cody, (class of 1907).

Pearl Alma Neas

As you continue your campus saunter, visualize some 400 uniformed men suddenly appearing, eager to learn how to be military officers. That’s what happened starting in 1944, and here’s a key figure to thank. Pearl Alma Neas was skilled at something women can often do: Connect people and unite them to get goals accomplished.

Pearl started out at SU as the President’s secretary in 1913 and worked her way up to being SU’s first-ever female registrar in 1923. She was deeply involved in all things SU, all things Georgetown and Williamson, and all things Democratic Party.

Pearl also built a strong friendship and working relationship with Lyndon Johnson and Lady Bird. She acted as an unpaid political consultant to LBJ, reports William B. Jones in his SU history. LBJ returned her esteem, noting that “I know of no woman whose judgment I admire more.”

Navy men march in front of the Cullen administration building, 1945; photo from the 1945 Southwestern University yearbook, The Sou’wester

Military V-12 grad Kenneth Matthews earned a Purple Heart in the Okinawa battle after training at SU.

SU was facing financial disaster during the WWII years because many male students were now serving in the military and families wary of wartime financial insecurity were reluctant to send their kids to college. Neas worked her connections with Johnson and others to score a V-12 Military Training Unit for the University during World War II. Nearly 400 soldiers came to SU, and the contract saved the SU financial day.

Dorothy went on from V-12 to get six degrees!

By the way, while the great majority of soldiers were men, there was at least one woman, and she was part of the program administration. Dorothy Imogene Popejoy was a Yeoman 3/c, and her assignment at SU was sparked by her patriotic passion after working at a Dallas diesel engine plant supplying the war effort. After helping run the V-12 program, Dorothy served in three other spots for the Navy. After that, she got three degrees in physical education, teaching and chairing the Women’s Physical Education Department at Michigan State University. After “retiring,” she got three more degrees, including her last at age 84 in Digital Media and Design. She spent her last years doing cat rescue in Arkansas and died in 2022 at age 100.

Nationwide, the V-12 program enrolled 125,000 soldiers at 131 colleges to supplement needed skilled officer needs, and also to prop up colleges decimated by student-age men and women serving in the war or in war-related industry. Pearl’s crucial dealmaking was a lifesaver that kept SU from a tailspin that could have meant closure.

When women were allowed into Southwestern in 1878, they took to it. By 1883—just five years later—women were nearly a third of the students: 127 women at SU along with 344 men.

At first, the women students were housed in the Ladies Annex, four blocks away from where the SU men were then. Fraternization with male students was severely curtailed, as noted in Placing Memory, a website about SU history. And punished! In April alone of 1883, 12 young women got demerits for contact with male students: some for corresponding with boys; others for conversing (at chapel, even!) with young men; others for walking and appearing in public with them. But only two young men got demerits. Is this sounding familiar? Sounds like women got punished for “wicked” behavior; most of the men got a pass for participating in same.

Ladies Annex women did everything segregated from men—certainly this gym class! Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

All the classes at the first Ladies Annex were women-only, and women were not allowed to take classes at the all-male main campus. SU administrators promised that while women could take classes and get degrees (only two-year degrees at first), this was NOT what many feared as too radical: “Coeducation.” But men sometimes wanted to take classes offered just to women over in the Ladies Annex, and of course women wanted to have full choices.

Male students wanted in on some of the cool all-women classes at the Ladies Annex. Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

There was much debate over mixing women and men in a classroom, but when the Ladies Annex was constructed in 1889 on what was then the outskirts of campus, SU started to quietly and slowly move toward coed classes. Classes were fully coeducational by 1903, a mere 25 years later.

Women students gather before the burned Ladies Annex building they escaped.

Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

The Ladies Annex, which in time came to be known as the Women’s Building, burned down in 1925. Laura Kuykendall, SU’s Dean of Women for 17 years, was lauded for her calm in getting all the young women out of the burning building.

That was yet another reason Laura was one of the most loved figures at SU. The female (and male) students adored her. Laura knew how to throw some dang fine parties. AND she was a feminist who encouraged women students to pursue whatever they wanted, not what the culture told them they should do.

The new Women’s Building replaced the old Ladies Annex, and it was built in 1926 at the site where the current Brown-Cody residence hall stands.

That’s where Laura continued to dream up gala parties that wowed students and attracted townspeople. The two-day May Fete featured student royalty, May basket hanging, pageants, and ball games. Her Christmas Carol Candlelight Service was an enchanting evening lit by candles and full of singing, music, readings, and a sit-down dinner. (The candlelit carol event is still an SU holiday tradition.)

Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

And Laura was happy to nurture fun gambits by students, such as this “Talking Club”. Whaddayaknow, these women favorited Men Who Listen! When Laura came, she was hired in the Department of Expressions. Here she is expressing.

Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

More importantly, Laura emphasized to her female students that they were capable of anything, and she encouraged them to undertake practical and nontraditional learning beyond the expected music and literature and domestic science. As Laura counseled, women used to have the choice of either marriage or spinsterhood, but today females have “the choice of a profession as a third way out.

Laura gets her Master’s degree.

And Laura modeled accomplishment for the women students as well. While she was Dean of Women, she completed a Masters degree in Sociology and Economics to become SU’s first female Masters grad. Plus she was the first licensed female driver on campus!

Laura DID get into some hot water for tolerating some swearing and cigarette smoking and dancing by female students, and she did some of that herself. She had a more relaxed attitude about male visitors to the dorm’s drawing room. Laura died suddenly of a stroke in 1935, and her funeral at Southwestern’s chapel was standing room only. In 1941, the Women’s Building was named Laura Kuykendall Hall.

In need of renovations, Kuykendall Hall was torn down in 1996. A Laura Kuykendall Garden was created on campus to honor her.

Southwestern women were lucky to get another inspiring Dean of Women. After Laura Kuykendall died suddenly, Mary Ann “May” Catt Granbery was named supervisor of women. She had pursued education at Wesleyan Institute, Mary Baldwin College, and the University of Chicago. She worked for the Y.W.C.A. in war-torn France and Greece.

May was a lifelong feminist and was the editor of The New Citizen, the publication of the Texas League of Women Voters. May and her husband John Granbery (also a staunch feminist and suffrage advocate) were good friends of Jessie Daniel Ames, the Georgetown suffragist and racial justice advocate (and SU grad).

Alma Thomas in front of the action-packed Alma Thomas painting; photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Take a look at the imposing entrance to the Alma Thomas Fine Arts Center on the building’s west side. You’ll find a large portrait of Alma inside in an austere gown looking demure. But don’t take her for a languishing lady of leisure. Here’s her real story.

Alma Thomas was born to a ranching family in Indian Territory in what became Oklahoma. She recalls that Lawton (in what would become Oklahoma) was just a collection of tents and saloons. She met rancher E. R. Thomas and married him in 1910. The two had two sons, and the family moved to a ranch near Midland.

Alma loved the ranching life. She often rode herd at roundups and she was as good as any cowpuncher. In 1923, her husband E. R. died from a fall off a windmill. She and the two teen sons kept the ranch going, and Alma and the boys moved to Austin, although they kept ownership of the ranch. All three of them went to UT, with Alma getting a degree in education and a master’s in economics. She was a principal and teacher for years.

Then Texas Tea—oil—was discovered on the ranch, and the family’s retained mineral rights proved to be a goldmine. A lifelong Methodist, Alma gave generously to Southwestern, funding what would be called the Alma Thomas Fine Arts Center with its Alma Thomas Theater.

Alma also supported numerous arts organizations after moving to Austin, including the Zachary Scott Theater and the Austin Symphony.

And she spent that oil dough with her first love: Traveling. She went to 127 countries around the world by 1971, including doing the Taj Mahal with gal pals and a trip to the North Pole where she had to land in a helicopter. Even at home, she didn’t slow down—at 60, she broke a wild horse so that her grandchild would have a safer ride.

So many townies have joined students and faculty to enjoy theater and music at Alma’s theater!

Her friend, the author J. Frank Dobie, called her a “salt-of-the-earth woman,” and she was funny. She preferred not to have hoopla and visibility around her donations, and she had not been enthusiastic about sitting for her portrait to be hung in the Alma Thomas Theater. When her portrait fell to the floor during a particularly rousing piano concert, Alma chuckled and commented, “I now belong to the big class of fallen women.”

Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Like most universities and medical schools, Southwestern started out being male-only. Mood-Bridwell Hall was for many years the male dorm. Here are some enthusiastic dorm dudes clinging to the walls of Mood.

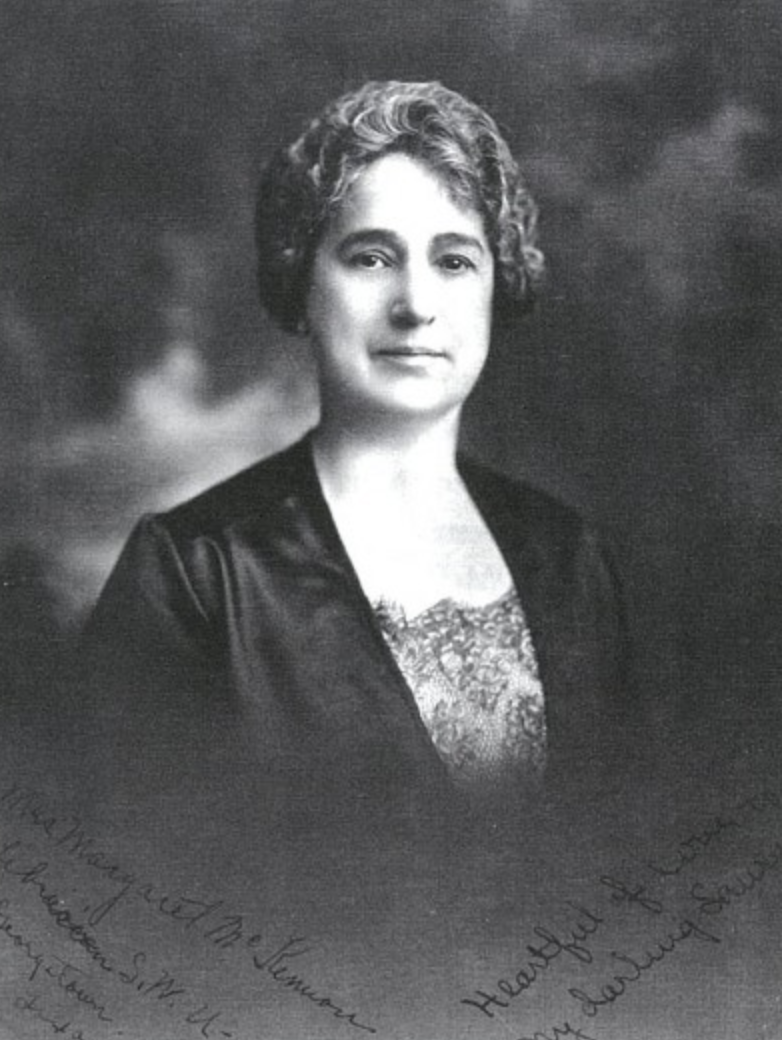

First fulltime librarian Margaret Mood McKennon; photo from the Southwestern University 1933 yearbook, The Sou’wester

The first female to graduate with a bachelor’s degree was Margaret Mood McKennon, the daughter of an SU founder, Dr. Francis Asbury Mood. So maybe Margaret had a little bit of pull with the admissions department, but she excelled all on her own. After graduating from SU, she taught in several mission schools in Mexico from 1895 to 1900 before becoming SU’s first full-time head librarian at Southwestern in 1903.

When Margaret came on board as librarian, the library’s holdings consisted of a personal set of books owned by one professor. Margaret dug in, and by the end of her 35-year tenure, she had gathered a diverse collection of 50,000 volumes. She would serve 41 years at SU.

Music in the Community: The Negro Fine Arts Project

SU students worked with faculty to start and maintain SU’s Negro Fine Arts program to teach kids music. Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

In 1946, Southwestern University was not integrated. Many of the SU students wanted change, but it was slow to come.

Nettie Ruth Brucks was a student who wanted change. As a girl, her family had lived in Goldthwaite, a town outside of Austin with a sign on the edge of town that read something like, “If your skin is black, don’t let the sun set on you in our town.” (These “Sundown Town” signs were used in many towns across the US—for Black and Latino and Asian people—and around the world. This sign is from apartheid-era South Africa, in English and Dutch Afrikaan.)

Elmina (passed 2010) wanted change.

Nettie Ruth hated this sentiment. She’d came to Southwestern to study music Christian Education and she belonged to the Student Christian Association (SCA). She and her music student friends Elmina Bell and Barbara Leon were angry when the SCA invited a Black man to speak, but then learned that the speaker couldn’t eat with them in the SU cafeteria. They went with him to eat potluck at the First Methodist Church down the street instead.

Barbara (passed 2011) also hated racism.

Nettie Ruth and other music students brainstormed a way to help Georgetown’s black children who were locked out of an education as good as the white kids. They came up with the idea of teaching music for free.

They’d been learning a teaching approach of teaching children in a group to play music, instead of one-on-one instruction. That method could help teach more students, they figured. They found strong leadership with their professors.

SU music professor Iola Bowden was their number one advocate in getting their plans to reality. “She was the glue that got it going and kept it going for 20 years,” recalls Nettie Ruth. Iola (learn more about her here) had already been teaching Black youngsters privately. She helped move along what became the Negro Fine Arts School, reaching out to find teaching space for the program at the classrooms of the First Methodist Church a few blocks west on University. She went to the teachers in the segregated schools and asked them to find students who’d like to participate.

Music professor Iola Bowden and two students

Iola taught middle-school and high-school Black students alongside the students. Nettie Ruth, Elmina, and Barbara were the student teachers the first year, and other students joined them in following years of volunteer teaching. The children could also take classes in voice, art, and handcrafts.

The Black students had been walking all the way from Carver School west of downtown. SCA students paid for a bus driver to pick up Black children and bring them to the after-school classes and they helped buy more pianos in addition to the piano provided by the Carver PTA. By 1950, the SCA, together with Southwestern and the Methodist Church and the Kings Daughters women’s club, started providing scholarships for all students of the Fine Arts School who wanted to study music.

Nettie Ruth married Morris Bratton, another Southwestern student who became a minister. She worked with him doing church duties, and then began teaching in the public schools. She was the first Methodist minister’s wife in the Southwest Texas Conference to work outside the home. Many young women thanked her for giving them permission to work and embark on a career.

Nettie Ruth has always been very involved in politics and nearly won a seat on the State Board of Education. She volunteered for many projects over the years to benefit people in central Texas. She continues to seek social justice on many fronts and inspire younger women.

Fine Arts program grads (L-R) Melza Smith, Birdie Shanklin, Paulette Taylor, and Alfred Fisher

And the Negro Fine Arts program created a wealth of benefits to hundreds of children. Over 200 students participated over the 20 years of the program. Many of the students went on to accomplish in the music sphere. Ernest Clark went to the Fine Arts program and went on to be the first African-American student to graduate from Southwestern in 1969. Clark became a music teacher who taught 36,000 students over his career. Southwestern renamed a residence hall for Ernest Clark, replacing it for the name of a board member and donor of the 1950s who had racist views about integration.

Ernest Clark, SU’s first Black grad

Several other Negro Fine Arts graduates went on to teach as well, such as Carl Finley Henry, who taught music for 33 years in Dallas schools to thousands of young people.

Celebrating the naming of the Ernest Clark Hall (L-R): Sharon Clark; Dr. Terri Johnson, former SU Assistant Dean for Multicultural Affairs; Ernest Clark; Paulette Taylor, president of Georgetown Cultural Citizen Memorial Association

Start your walk at the Lois Perkins Chapel, at the top of the half-circle promenade on campus. We’ll circle around campus for a .5 mile stroll. For a look at a few SU-linked spots off campus, you’ll clock 1.7 miles when you come back to the Chapel.

☛ Lois Craddock Perkins lives on in her beautiful chapel, but also in the women students whose college path was made possible by Lois Perkins Aid Fund for Young Women. The Chapel may not be open when you stop by, but look for special occasions to visit and see the lovely interior, such as the 105-year-old tradition of Candlelight Service to celebrate Advent and the Christmas season. When you do, thank Phoebe and Laura.

Phoebe Eleanor Jones Bishop’s husband was Dr. Charles McTyeire Bishop, the University’s president from 1910 to 1921, and Phoebe made Candlelight night happen, with the assistance of former Dean of Women Students Laura Kuykendall, who served Southwestern from 1914 to 1953.

At the 1915 service, a processional of 125 women filed into the Chapel amidst a congregation illuminated by candles singing Christmas hymns and accompanied by the Southwestern University Orchestra. Methodist pastors prayed, everyone sang holiday carols, the Christmas story was read, and everyone had a buffet dinner.

☛ If you’re facing the Chapel, go around the corner to your right to see the Madonna and Child sculpture. Eminent sculptor Charles Umlauf created this; check out the Umlauf Sculpture Garden in Austin.

Elizabeth Perkins Prothro

☛ Continue to your right around the promenade. Stop at the Charles and Elizabeth Prothro Center for Lifelong Learning. The building honors Charles Prothro and Elizabeth Perkins Prothro, the daughter of Lois Craddock and Joe Perkins. Elizabeth also focused her generosity on higher education here at SU, Southern Methodist University, and several other universities.

Charles and Elizabeth Prothro building

She bettered her hometown of Wichita Falls with scholarships at Midwestern State University and funding for the Wichita Falls Museum and Art Center and the Riverbend Nature Center. A published photographer, she supported the art of photography with the Elizabeth Perkins Prothro Photography Gallery at the Harry Ransom Center at UT, a photography book imprint, and more.

☛ Turn left after the Charles and Elizabeth Prothro building, and head up the sidewalk to the residence halls. Look to the hall on the left, Cody-Brown. Here’s about where the Women’s Building and then the Laura Kuykendall Hall was located.

The May Festival in 1946, with Maypole, dancing, and general revelry

Imagine all the learning and fun and new horizons for SU women over the years!

☛ Look at the residence hall at the top of this cul-de-sac: It’s Ernest Clark Hall, named after the first Black SU graduate who went on to educate some 36,000 students in his career.

☛ Turn around and head back down the sidewalk toward the Alma Thomas Fine Arts Center. If the building is open (campus buildings are at certain times only accessible to students), walk in. If you keep walking after traversing the long hall, look to your left for the large portrait of Alma Thomas close to the front windows near the Sarofim School of Fine Arts entrance. Hopefully she and her portrait won’t ever again be one of Those Fallen Women!

☛ Look around the lobby and see the plaques honoring donors, including several women. Here’s a bit about the life of just one: Genevieve Britt Caldwell, SU class of 1942. She grew up in the windswept Panhandle and attended a one-room schoolhouse. She followed a family tradition of heading to SU, and graduated with honors in 1942.

Genevieve looked for a job to support the war effort, and worked at the Pantex Ordnance plant. She married torpedo bomber pilot “Red” Caldwell, who had a saddle-making business. While she raised two children, she gave her energies to improve many things Amarillo, including music, art, the history museum, support for people with cancer, and the Boy and Girl Scouts. She was a tireless SU recruiter, sending over 135 students to study here. Genevieve died at 98 in 2003.

Women’s Studies Alcove

☛When you come out the west side of Alma Thomas, head left down the sidewalk to see the original entrance with Alma’s name. Head west past the fountain and turn right to enter the Smith Library’s main door.

Go upstairs to the cozy Women’s Studies Alcove and browse their awesome women-centric books.

☛ Go left after leaving the main door of the library, and then left again towards the beautiful new Fondren-Jones Science Hall. A tip of the hat to Ella Fondren, who funded the original Fondren Science Hall in 1954. Ella had married Walter William Fondren, who was one of the founders of Humble Oil company, which then became Exxon.

Ella Fondren

But as William Burwell Jones writes in the fascinating SU history, To Survive and Excel: The Story of Southwestern University, Ella worked with Walter and also invested on her own early on in a venture that became Texaco. After Walter died, Ella wrote her own check for the Fondren Science Hall.

☛ Turn the opposite direction from Fondren-Jones to face the majestic old Mood-Bridwell Building. Built in 1908, Mood was a man-palace for many years, but was at other times an all-women’s residence and the residence for many of the Naval trainees during the war years.

☛ Turn around again and head toward University Avenue on the sidewalk between Fondren-Jones and SU’s oldest building, the Cullen administration building.

At the end of the sidewalk, look left to see a low cement stand with a smooth top. This is where for decades this marker commemorated Georgetown’s Woman’s Club. Sometimes the women met on campus. At this time, the location of the marker is unknown.

See more about the huge impact of our women’s clubs over the years here.

Come back out toward the SU clock and head north, back toward where we started. Walk to the left of the Mood-Bridwell building toward the Physical Plant. Give deep thanks to all the employees who keep the air conditioning flowing during the summer and everything running spit-spot. Bow to the housekeepers who keep all the buildings clean and inviting, and all the kitchen folks who keep everyone fed.

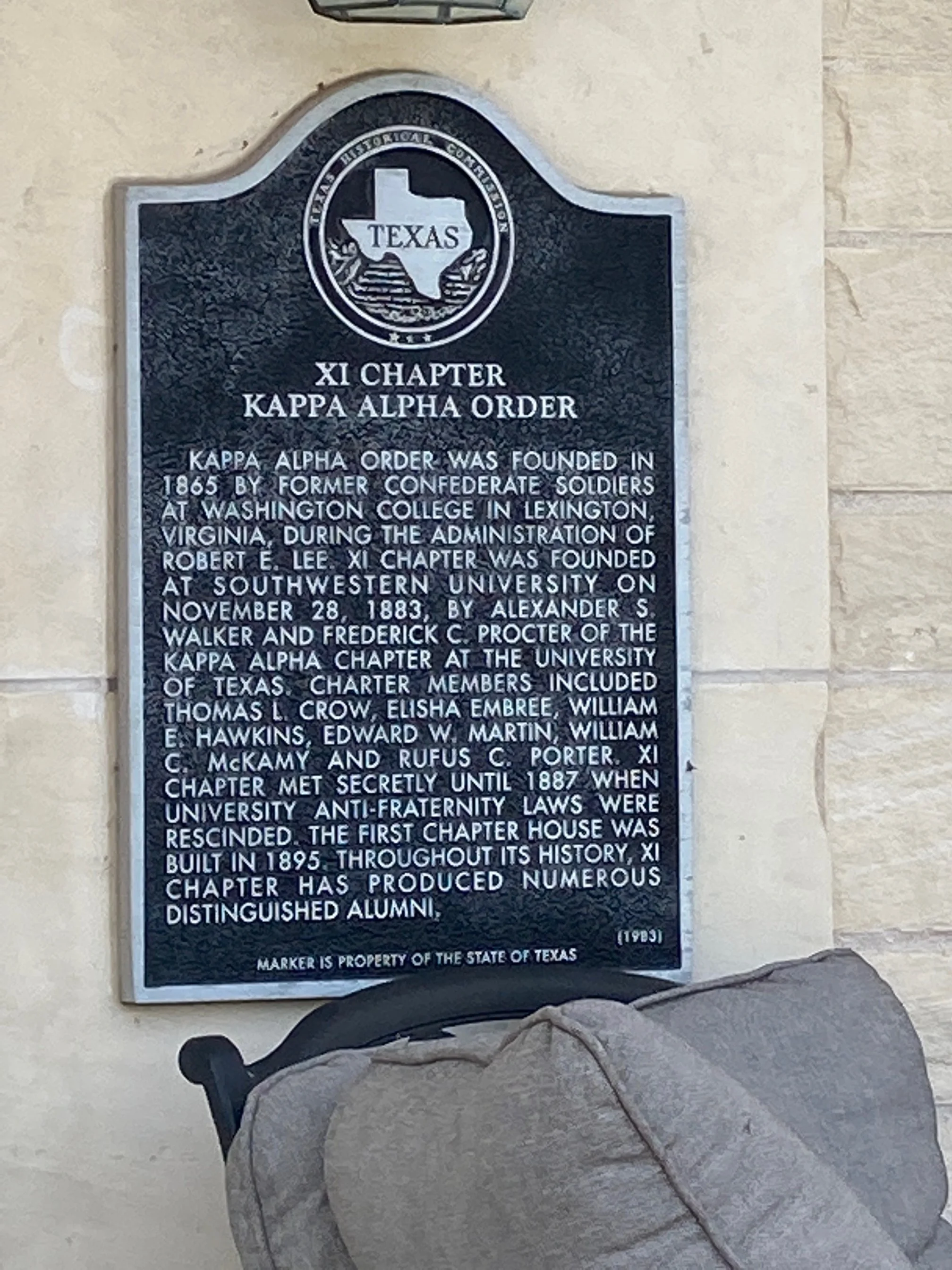

☛ Get ready for some Frat House action! Just beyond the Physical Plant is the house of the Phi Delta Theta, one of SU’s four fraternities. Head to the left of the House and to your left will be the Kappa Alpha House. As the marker on its porch notes, KA was founded in 1865 by former Confederate soldiers when Dixie was headed by Robert E. Lee.

Over the years, the chapter here and others among its 120-some chapters have been criticized for reveling in its Confederate roots, hosting antebellum formals and reciting chants lamenting the Union victory in the Civil War. More recently, three Kappa Alphas from the University of Mississippi posed with guns at a memorial for Emmett Till, the Black teenager whose horrific lynching made him a namesake of the federal anti-lynching bill passed in 2022.

Now the SU chapter has drawn national attention for refuting their Confederate past. SU members demanded that the fraternity nationwide drop its association with Lee and investigate the racial harms they say Kappa Alphas have inflicted. The action was initiated in 2019 by Noah Clark, the first Black student graduating as an active KA member. Kappa Alpha Order’s national organization then suspended the SU chapter for a year, as well as other chapters calling for similar actions.

Margarett

Cross McKenzie Drive to see the Kappa Sigma House to the right and the Pi Kappa Alpha House on the left. Pass between these frat houses to approach the Herman Brown Residence House, and give a salute to Herman’s spirited and influential spouse, Margarett (see above for more on her). Take the path to the next building that leads us to another notable SU woman, Mary Moody Northin.

Moody-Shearn Residence Hall

Mary was born into a wealthy Galveston family in 1892, and as such made her debut into society and was tutored at home. However, she was also a bustling businessgirl early on with her Great American Chicken Company, where she sold eggs and chickens to family and friends. As a married woman with no chldren, she’d meet with her dad nightly to discuss the doings of the family enterprises. William L. Moody, Jr., was grooming Mary, not his sons, to take over the family empire.

When her dad died, Mary became president of their many holdings, including a national insurance company, bank, and a newspaper publishing company. She chaired or would chair some 50 organizations, including the family foundation, their cotton company, hotel chair with nearly 40 hotels, and a ranch company with holdings in three states.

Mary Moody Northen

Mary established the Mary Moody Northen Endowment in 1964. She funded the construction of the Moody-Shearn Hall, adding her grandfather’s name in its naming. John Shearn graduated in 1845 from Rutersville College, a college that merged into Southwestern when it began in 1873.

Mary also used her Foundation to build the Texas A & M Maritime Academy and preserve historical properties such as the 1877 ship Elissa, turn an abandoned depot into a railroad museum, and turn her mansion into a museum. Tour the Moody Mansion on Galveston Island to see the roots of this ambitious woman!

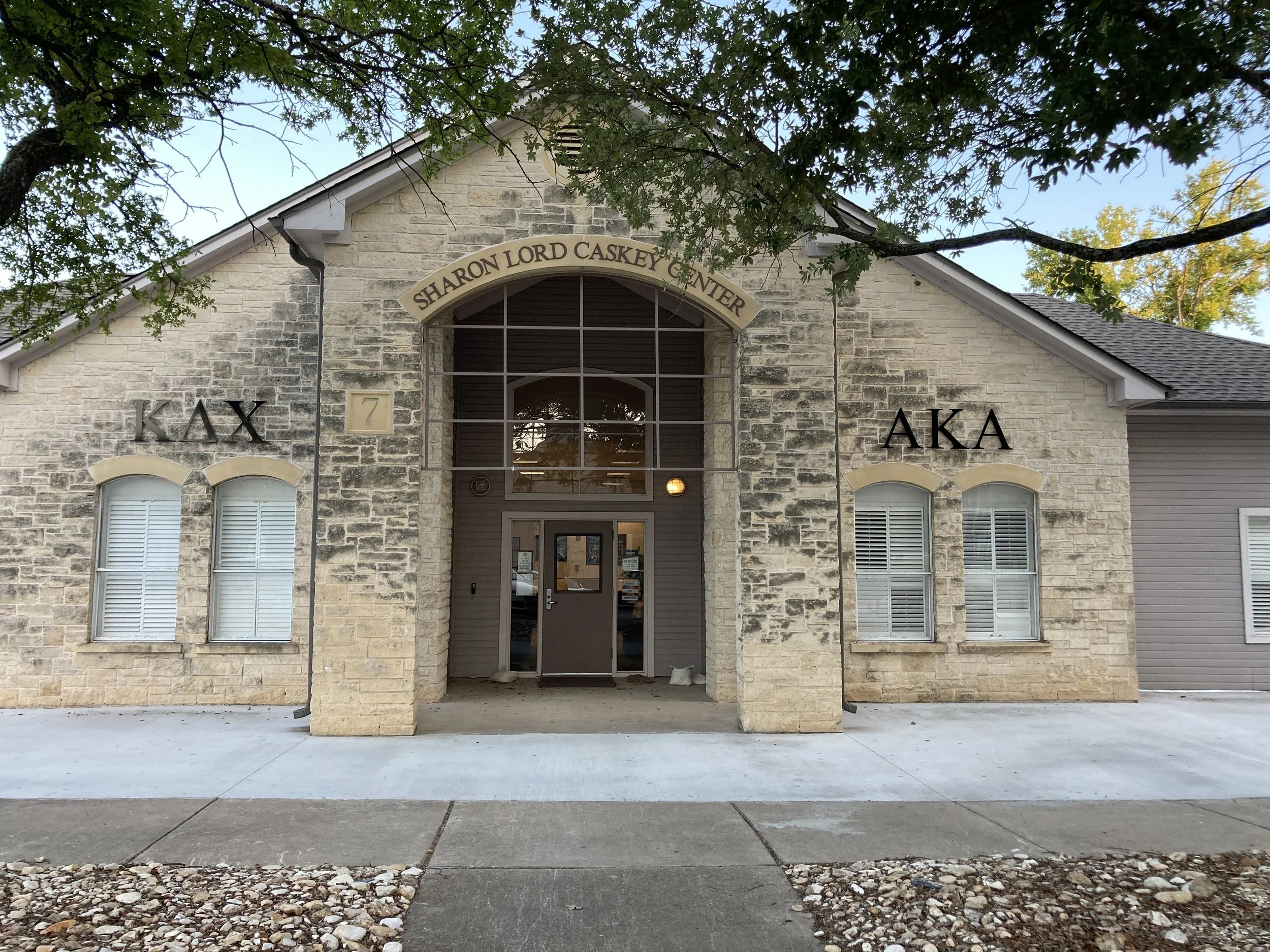

☛ Keep looking north as you leave Mary’s dorms. See that modest building on the corner with the Greek letters on the wall? That’s the Sharon Lord Caskey Center, funded by businesswoman Sharon (her parents, Grogan and Betty Fowler Lord, are the namesakes of the student housing beyond Sharon’s center.)

This building is where SU’s sororities are allowed to meet in separate chapter rooms. In contrast to the voluminous houses afforded the fraternities, SU sorority sisters have had to fight for a place to meet. Sorority members who are salty over their diminished space are told that the lack of sorority houses on campus springs from a Williamson County statute that way back when limited the number of women living in the same house. The fear was that such houses would become places of prostitution.

Various SU administrators also feared parent wrath when delicate females were in their own houses and could more easily flout the heavy-handed oversight of said females. Plus, by the time the fraternities took up their space, women were told that there wasn’t space to build sorority houses.

Nevertheless, the women persisted, going back to the start of the 1900s. Women students including Jessie Daniel (who’d later lead the suffrage battle in Williamson County and found an anti-lynching organization in Atlanta) asked then president Robert Hyer to start a sorority; they were refused. Two years later, three sororities were allowed, including Alpha Delta.

Over the years, sororities met at the Women’s Building, later called Laura Kuydendall Hall. Now they meet here for meetings at their Center room, and arrange to hold their parties and formals elsewhere. Many students still believe that Greek-minded women should have their own houses, but as this 2022 student newspaper report notes, it may never happen.

Now cross Wesleyan Drive and look for the spires of Lois Perkins Chapel to return to your tour beginning.

SU in the Community

Want to see some nearby sites where SU actually began and where important racial justice work was done? Then take a stroll down University Avenue. But before you head west on University, look across the street to the small white building that’s slated to be replaced by a student pub.

That mission harkens back to when students flocked to sip sodas and sashey around in sock hop socials, the Pirate Tavern. The joint opened in 1930, the Tavern was quite the draw. In 1943, SU bought the Tavern and hosted a soda fountain and post office until the last soda was sipped in 1957. It was used for various SU program offices since.

☛ Head west (toward downtown) on University (wonder why it was named that?) to see where SU started. Stop when you get to College Street. Guess why it’s called College Street. Yep, because that’s where Southwestern University—called Georgetown College initially—started.

Look at the grand space between College and Ash and going way back four streets to 8th street. Check out the Southwestern marker in front of Hammerlun.

Ann Morris Giddings

Notice the mention of Giddings Hall. Give a thanks to Ann Morris Giddings, who not only funded the boys’ dorm which was first called “Helping Hall” but also funded other cottages for female and male students of lesser means. Ann, married to Brenham baron Jabez Demming Giddings, funded the Girl’s Cooperative Home and several other cottages for students who got free lodging and board at cost so they could afford to go to SU. In gratitude, the students insisted that the dining hall adjacent to Helping Hall be named Giddings Hall.

☛ Head up Ash and circle right on 8th St. to continue back to SU. Follow 8th St. as it curves left on Holly to meet 9th. Turn right and go to the train tracks. Picture what once was: the Katy railroad station—very popular with SU students to hop on and head off to Austin or another destination!

☛ Cross the tracks and go right on Maple to head back to Lois Perkins Chapel.